New Study: Do Flashcards Work?

TLDR

A new paper just published may give more evidence that flashcards are both (very) effective and under-utilised

A 2021 meta-analysis appears to find that only 2 methods of studying are highly effective (all others are of low or moderate effectiveness)

Majority of students seem to consistently use the lowest-effectiveness methods (which will likely only get worse with the rise of AI)

Some new shaeda updates

A very small request at the end

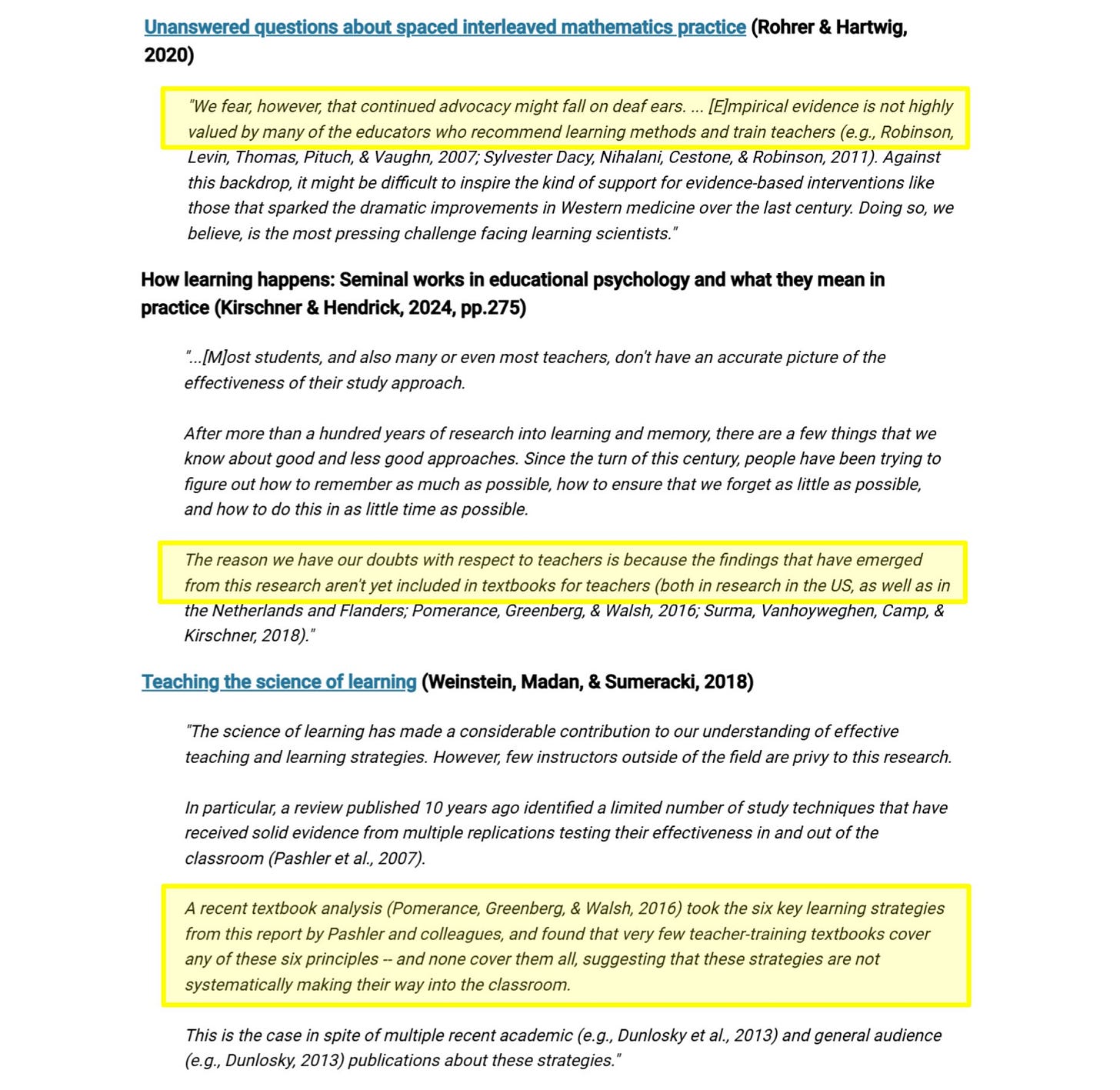

Research seems to indicate that a large percentage of teachers during their training were not made aware of the research on effective studying and learning

Are Flashcards Effective?

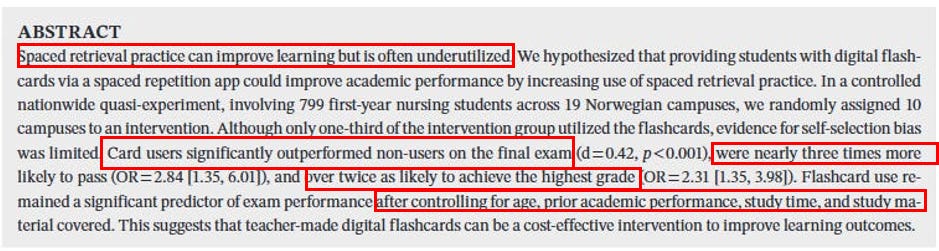

A new study by Ingebrigtsen and colleagues testing the effectiveness of flashcards on student learning was just published the other day (Ingebrigtsen et al., 2025). The discussion segment, which begins at the bottom of page 10, is particularly insightful without needing to read the entire paper necessarily. I will paste the Abstract below.

The below is a very quick summary:

Students were randomised into whether they were placed into the flashcard group or not

The exam was a first-year university exam covering Anatomy, Physiology and Biochemistry with a historically high failure rate of ~20-25%.

Flashcard users scored on average +7.6 points greater on the final exam (out of 100)

Flashcard users were nearly 3× more likely to pass

Flashcard users were over 2× more likely to get an A

The relationship between flashcard use and greater exam performance was maintained after adjusting for potential confounders (age, effort, study duration etc)

Potential limitations did exist, such as low adoption rate of flashcards.

I will paste some screenshots of the paper that are of most relevance below for those interested in further reading without wanting to be overwhelmed by the full paper.

Do Related Studies Find Similar Results?

The study above builds on previous papers which also found positive effects of spaced practice/flashcards/testing:

This paper concluded “A total of 87% of flashcard users found the flashcards to be helpful, and 83% of flashcard users would recommend the flashcards to someone else. Flashcard usage was not associated with final exam scores.” (Sun et al., 2021)

Some notes here:

They were restricted from actually publishing the exam results

Flashcards were only used for a short period of time, thus the full effects were not likely to have fully materialised yet

The authors of this paper write the following in an ‘Essentials’ segment (Deng, Gluckstein & Larsen., 2015):

This paper concluded with “Repeated testing with feedback appears to result in significantly greater long-term retention of information taught in a didactic conference than repeated, spaced study. Testing should be considered for its potential impact on learning and not only as an assessment device.” (Larsen, Butler & Roediger 3rd., 2009)

This paper concluded “Spaced education significantly improved composite end-of-year test scores…Spaced education consisting of clinical scenarios and questions distributed weekly via e-mail can significantly improve students' retention of medical knowledge.” (Kerfoot et al., 2007)

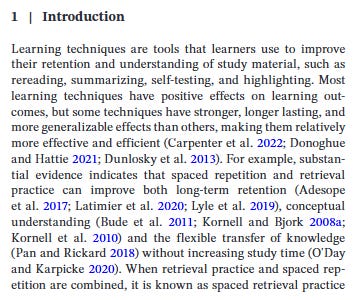

Remember, at a fundamental level all flashcards are doing is easily implementing Spaced Practice and Self-Recall (a.k.a. retrieving from memory with minimal (0) assistance)

For more on these 2 methods, I will paste some quotes from a meta-analysis performed in 2021 below.

2021 Meta-analysis on Effective Study Techniques

The below is directly quoted from this Meta-analysis where the authors are referring to a previous meta-analysis done in 2013.

This article outlines a meta-analysis of the 10 learning techniques identified in Dunlosky et al. (2013a), and is based on 242 studies, 1,619 effects, 169,179 unique participants, with an overall mean of 0.56.

The most effective techniques are Distributed Practice and Practice Testing and the least effective…are Underlining and Summarization

The authors of a previous meta-analysis categorised 10 techniques into three groups based on whether they considered them having high, medium or low support for their effectiveness in enhancing learning.

High support ✅

Practice Testing

Distributed Practice

Moderate support

Elaborative Interrogation (generating an explanation of a fact or concept)

Self-Explanation (where the student explains how new information is related to already-known information)

Interleaved Practice (implementing a schedule of practice mixing different kinds of problems within a single study session).

Low support

Summarization (writing summaries of to-be-learned texts)

Highlighting/Underlining (marking potentially important portions of to-be-learned materials whilst reading)

Keyword Mnemonic (generating keywords and mental imagery to associate verbal materials)

Imagery use (attempting to form mental images of text materials while reading or listening)

Re-Reading (restudying text material again after an initial reading)

In an accompanying article, Dunlosky et al. (2013b) claimed that some of these low support techniques (that students use a lot) have “failed to help students of all sorts” (p. 20), the benefits can be short lived, they may not be widely applicable, the benefits are relatively limited, and they do not provide “bang for the buck” (p. 21).

Practice Testing is one of the two techniques with the highest utility. Practice Testing instead involves any activity where the student practices retrieval of to-be-learned information, reproduces that information in some form, and evaluates the correctness of that reproduction against an accepted ‘correct’ answer. Any discrepancy between the produced and “correct” information then forms a type of feedback that the learner uses to modify their understanding. Practice tests can include a range of activities that students can conduct on their own, such as completing questions from textbooks or previous exams, or even self-generated flashcards. According to Dunlosky et al. (2013a), such testing helps increase the likelihood that target information can be retrieved from long-term memory and it helps students mentally organize information that supports better retention and test performance. This effect is strong regardless of test form (multiple choice or essay), even when the format of the practice test does not match the format of the criterion test, and it is effective for all ages of student. Practice Testing works well even when it is massed, but is even more effective when it is spaced over time. It does not place high demand on time, is easy to learn to do (but some basic instruction on how to most effectively use practice tests helps), is so much better than unguided restudy, and so much more effective when there is feedback about the practice test outputs (which also enhances confidence in performance).

Many studies have shown that practice spread out over time (spaced) is much more effective than practice over a short time period (massed)–this is what is meant by Distributed Practice. Most students need three to four opportunities to learn something (Nuthall, 2007) but these learning opportunities are more effective if they are distributed over time, rather than delivered in one massed session: that is, spaced practice, not skill and drill, spread out not crammed, and longer inter-study intervals are more effective than shorter. There have been four meta-analyses of Spaced vs. Massed practices involving about 300 studies, with an average effect of 0.60 (Donovan and Radosevich, 1999; Cepeda et al., 2006; Janiszewski et al., 2003; Lee and Genovese 1988). Cepeda et al. (2008) showed that for almost all retention intervals, memory performance increases sharply with the length of the spacing interval.

Further, Spaced Practice is more effective for deeper than surface processing, and for all ages. Rowland (2014) completed a meta-analysis on 61 studies investigating the effect of testing vs. restudy on retention. He found a high effect size (d = 0.50) supporting the testing over restudy, and the effects were greater for recall than for recognition tasks. The educational message is to review previously covered material in subsequent units of work, time tests regularly and not all at the end (which encourages cramming and massed practice), and given that students tend to rate learning higher after massed, educate them as to the benefits of spaced practice and show them those benefits.

A follow-up and more teacher accessible article by Dunlosky et al. (2013b) asks why students do not learn about the best techniques for learning. Perhaps, the authors suggest, it is because curricula are developed to highlight content rather than how to effectively acquire it; and it may be because many recent textbooks used in teacher education courses fail to adequately cover the most effective techniques or how to teach students to use them. They noted that employing the best techniques will only be effective if students are motivated to use them correctly but teaching students to guide their learning of content using effective techniques will allow them to successfully learn throughout their lifetime.

The authors of this paper then essentially tested again this 2013 meta-analysis to calculate an individual effect size for each of the 10 learning techniques.

Method:

Research syntheses aim to summarise past research by estimating effect-sizes from multiple, separate studies that address, in this case, 10 major learning techniques. The data is based on the 399 studies referenced in Dunlosky et al. (2013a). We removed all non-empirical studies, and any studies that did not report sufficient data for the calculation of a Cohen’s d. This resulted in 242 studies being included in the meta-analysis, many of which contained data for multiple effect sizes, resulting in 1,620 cases for which a Cohen’s d was calculated (see Figure 1).

Results:

The below is a quick overview of this Table with slightly more detail:

In the first column we see the study technique.

In the second we see what the 2013 meta-analysis classified each as in terms of effectiveness.

The third, # Cases, represents the total number of effect sizes. Since a single study can report multiple results (e.g., for different groups or at different times), this number can be higher than the number of studies. We can see that there’s much more data for the top 2 techniques.

The fourth column, Unique N, is the total number of unique participants (subjects) across all studies for that technique. N is a standard abbreviation for number. Using a "Unique N" ensures individuals are not counted multiple times, giving us the true sample size. Generally, a larger N is better as it increases the statistical power and precision of the results.

The fifth, d (short for Cohen’s d), is arguably of most relevance and hence why I’ve highlighted it. This is the actual calculated effect size. It attempts to tell us how much of an effect did the study method have on knowledge retention. Below is loosely how to interpret:

d of <0: Negative effect.

d of 0: No effect.

d of >0: Positive effect;

~0-0.2 = Small positive effect

~0.2-0.5 = Moderately positive effect

~0.8 = ~High positive effect

The sixth column, SEM (Standard Error of the Mean), attempts to quantify the precision of the calculated mean effect size. It represents the estimated SD of the sample means if you were to re-run the study multiple times. It essentially serves as a measure of confidence in the result: the lower the SEM, the more precise the estimate and the more likely it is that our sample mean accurately reflects the true population mean.

The seventh column, Q, measures how much the results of the grouped studies varied from each other. I.e., how different their findings were. We can see that there was a lot of variation. For more on this would be beyond the scope of this email, but the authors address it in their paper with further analyses.

And lastly we have I² (I-squared) which is telling us what percentage of total variation in the results is due to the differences between studies rather than random chance. Again, more on this would be beyond the scope of this email but can be found by reading through the paper.

The below is now back to quoting from the paper:

The purpose of the current study was twofold: to provide empirical estimates of the effectiveness of the 10 learning techniques, and second, to empirically evaluate a range of their potential moderators.

The technique with the lowest overall effect was Summarization. Dunlosky et al. (2013a) note that it is difficult to draw general conclusions about its efficacy, it is likely a family of techniques, and should not be confused with mere copying. They noted that it is easy to learn and use, training typically helps improve the effect (but such training may need to be extensive), but suggest other techniques might better serve the students.

In their other article (Dunlosky et al., 2013b), the authors classified Summarization as among the “less useful techniques” that “have not fared so well when considered with an eye toward effectiveness” (p. 19).

What is now most startling is that it appears quite consistently that the least effective techniques are actually the most used by students when asked.

Urrizola, Santiago & Arbea in their 2023 paper titled “Learning techniques that medical students use for long-term retention: A cross-sectional analysis” write the following:

Remember that the authors of the first study on flashcard effectiveness also cited other studies and wrote similar:

Further Reading

For more reading on this for those interested, I can strongly recommend the following books which are all both recent and based on research.

Shaeda

Japanese and Mandarin are undergoing testing ‘2.0’ with teachers (early feedback is great so far).

Flashcard generation time is now around 1-1.5 seconds using the default model.

No other flashcard app is this fast, accurate, simple to use and, most importantly, actually validated for languages and/or topics.

The 1 Minute Shaeda Survey is still open for feedback on useful features you would like to see

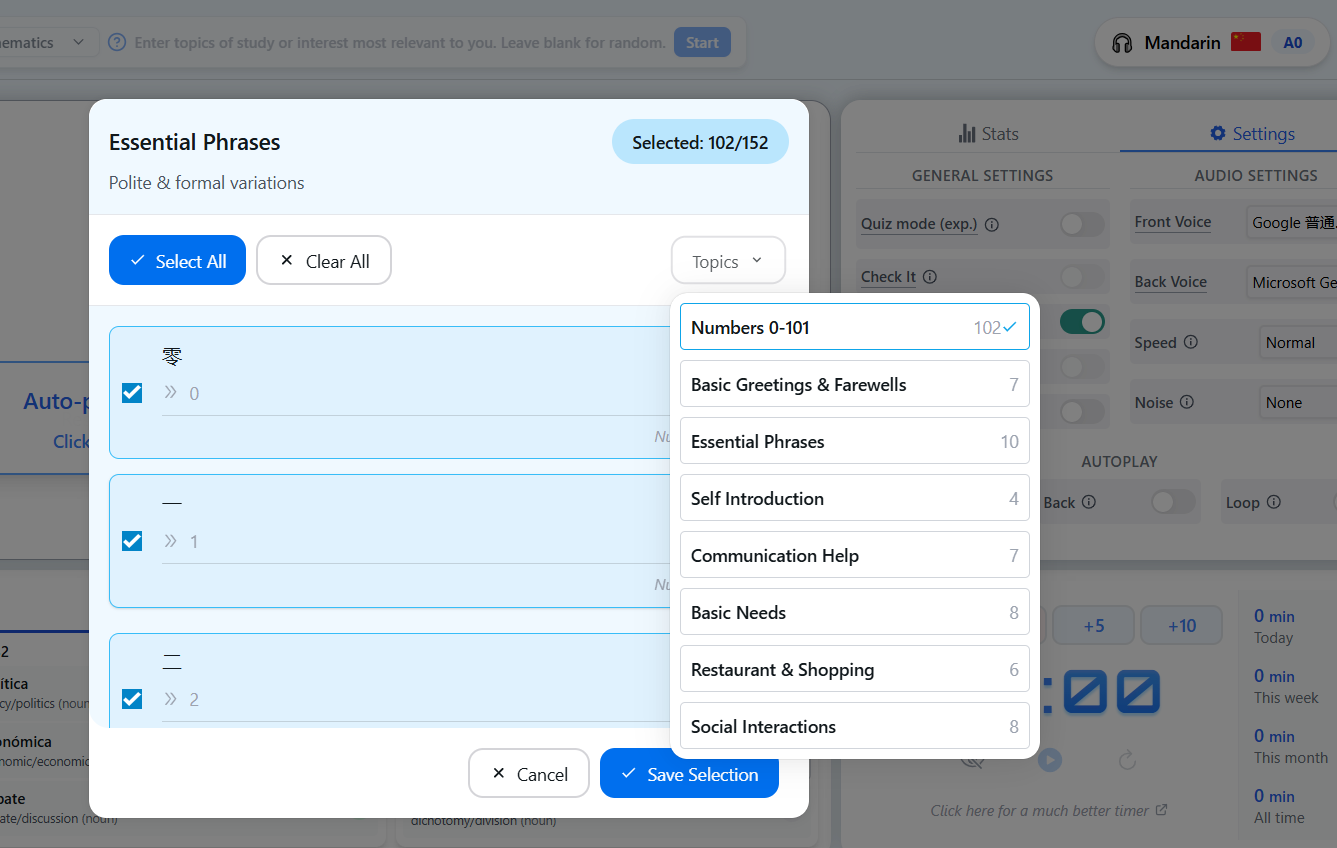

For language learning at level A0, all languages now have numbers 0-101 available

On release of shaeda, level A0 will be completely free. This level contains the core 50 words/sentences and numbers 0-101. This will most likely mainly be for those who are perhaps new to flashcards for language learning or perhaps are simply going on holiday and want to be able to say just x amount of key words/phrases (which, for the record, you probably should. Not only will you make the locals’ day but you will probably also be treated to things most aren’t as they will appreciate you have gone out of your way to learn)

For non-language learning purposes, for all validated-topics I will be adding something similar to the above ‘A0’ level whereby the core 50 need-to-knows for each subject at a very basic level will be available for free (I.e., “What force causes objects to ‘drop’?”) and (of course) will have been validated by teachers of said subjects.

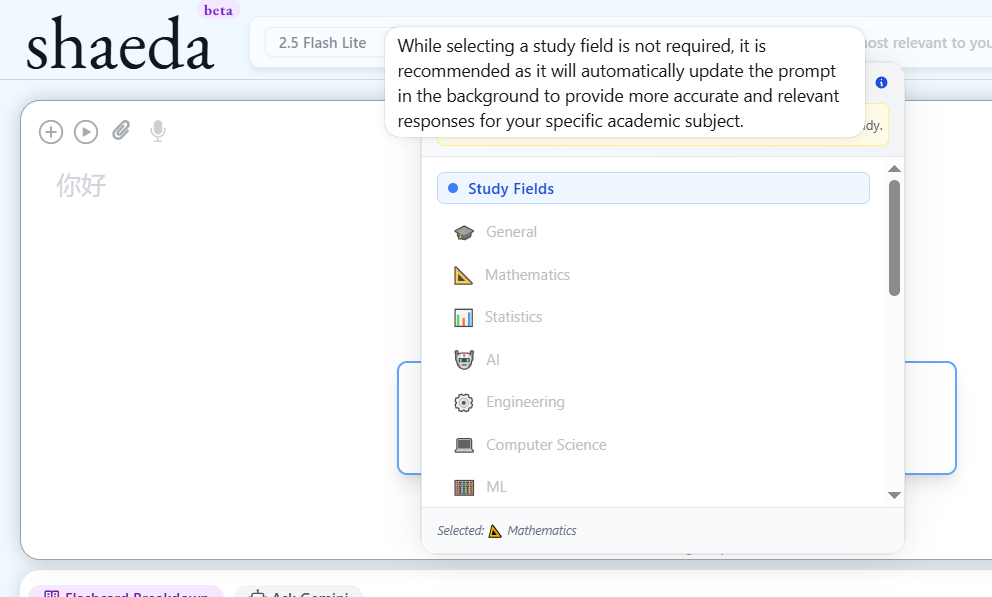

Model selection and also Topic selection (if using for Academic study) can be seen below

That is everything! Hopefully this may be helpful and reassuring to many who are confused about flashcards and/or wondering what the research finds regarding their effectiveness.

Next week I plan on writing about some common complaints and/or worries over using flashcards (friction in finding appropriate cards, confusion in setting up, concerns that flashcards are only usable for random fact memorisation etc).

If you know someone who may be interested in the research shared in this post (particularly the just-released study I mentioned at the beginning) or the future post on common concerns over flashcards, please do consider sharing this with them to help their education and learning too.

Housekeeping

Due to this Substack being new, the first update I sent out last week for some reason only reached about 40% of recipients’ inbox, with it going into spam for 60% (including mine, amusingly). According to Substack, encouraging readers to reply to the email will fix it. So, I guess, if you have any questions at all (or if you’d just simply like to help), please do consider replying directly to this email - I read them all!

Thank you, & Happy Learning🧠

- shaeda

Awareness in Schools

Bibliography

Ingebrigtsen, M., Odden Miland, Å., Basteen, J., & Grom Sæle, R. (2025). Effective, scalable, and low cost: The use of teacher-made digital flashcards improves student learning. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 39(1), e4254. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.4254

Donoghue, G. M., & Hattie, J. A. C. (2021). A meta-analysis of ten learning techniques. Frontiers in Education, 6, Article 581216. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.581216

Urrizola, A., Santiago, R., & Arbea, L. (2023). Learning techniques that medical students use for long-term retention: A cross-sectional analysis. Medical teacher, 45(4), 412–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2022.2137016

Larsen DP, Butler AC, Roediger HL 3rd. Repeated testing improves long-term retention relative to repeated study: a randomised controlled trial. Med Educ. 2009 Dec;43(12):1174-81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03518.x. PMID: 19930508.

Kerfoot BP, DeWolf WC, Masser BA, Church PA, Federman DD. Spaced education improves the retention of clinical knowledge by medical students: a randomised controlled trial. Med Educ. 2007 Jan;41(1):23-31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02644.x. PMID: 17209889.

Sun M, Tsai S, Engle DL, Holmer S. Spaced Repetition Flashcards for Teaching Medical Students Psychiatry. Med Sci Educ. 2021 Apr 6;31(3):1125-1131. doi: 10.1007/s40670-021-01286-y. PMID: 34457956; PMCID: PMC8368120.

Deng F, Gluckstein JA, Larsen DP. Student-directed retrieval practice is a predictor of medical licensing examination performance. Perspect Med Educ. 2015 Dec;4(6):308-313. doi: 10.1007/s40037-015-0220-x. Erratum in: Perspect Med Educ. 2016 Dec;5(6):364. doi: 10.1007/s40037-016-0312-2. PMID: 26498443; PMCID: PMC4673073.

Piza, F., Kesselheim, J. C., Perzhinsky, J., Drowos, J., Gillis, R., Moscovici, K., Danciu, T. E., Kosowska, A., & Gooding, H. (2019). Awareness and usage of evidence-based learning strategies among health professions students and faculty. Medical teacher, 41(12), 1411–1418. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2019.1645950

Demekash, A. M., Degefu, H. W., & Woldeab, T. A. (2024). Secondary school EFL teachers' awareness for formative assessment for effective learning. Heliyon, 10(19), e37793. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e37793